I shut down my AI-powered startup. What went wrong?

Hint: It wasn't the AI.

Disclosure: This article was written by me, a human, while winding down my latest AI-powered development project. The StackDigest timeline was created with assistance from NotebookLM, and Claude Sonnet 4.5 edited the whole thing.

I ran through my shutdown checklist for the last time this morning:

Delete production environment and data source: done.

Delete development data source: done.

Update code snippets on GitHub to avoid any use of Substack’s API: done.

Set up redirect for stackdigest.io: pending Cloudflare nameserver update.

Archive code, just in case Substack ever changes its TOS or begins a developer outreach program: done.

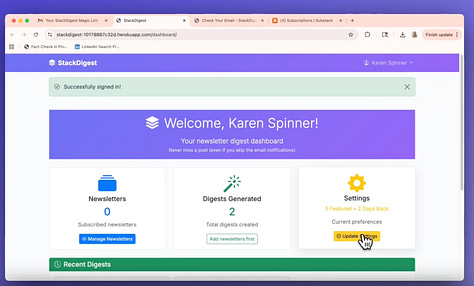

For those of you who are new here, I recently made the difficult decision to shut down StackDigest, my little one-person startup. And unlike the first AI product I built—the dearly departed Good Bloggy writing platform, which literally had no users except for me and a few crazy kids desperate to cheat on their essays—the StackDigest community grew to 165 users, many of whom actively tested it and even used it regularly.

And, while it had some bugs and flaws, it was a genuinely helpful tool.

I used it to find newsletters for the 5 Under 500 series that featured interesting publications with fewer than 500 subscribers. While I will continue this series, I will publish much less often (perhaps every few months?) because manual curation without StackDigest is so time-consuming.

The She Writes AI Community used it to create weekly digests highlighting recent articles from their 500+ members. (This may be able to continue using a limited, open-source version of the digest feature that relies on RSS feeds.)

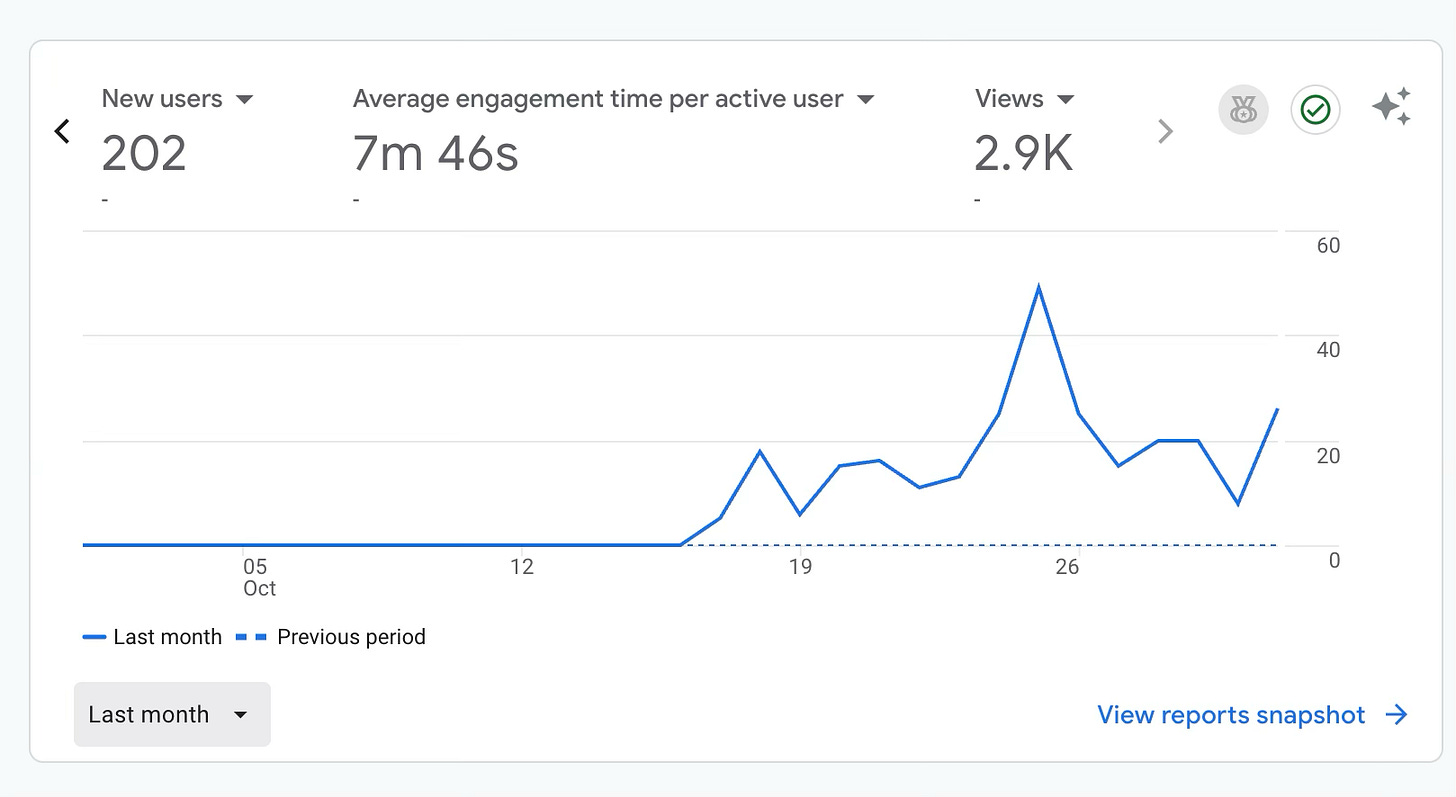

And I heard from many creators about how its Deep Dive newsletter analysis report helped them better understand publishing trends in their space. The weekend I released that feature, my production environment crashed from too many concurrent users; it’s the moment every builder dreams of.

But a legal and compliance review, which I had initiated myself as a sanity check before investing more significant time and money into a real product launch, brought my dreams back to earth and marked the end of the StackDigest journey.

Now let’s take a step back, see exactly how I got here, and where I went astray…as well as the many valuable things I learned that I will take to my next project.

What was StackDigest?

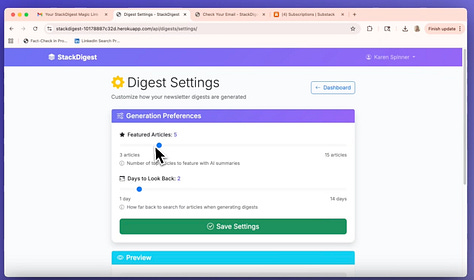

StackDigest started as a simple solution to a problem I had two weeks into my Substack journey. I had subscribed to hundreds of newsletters (I was a “follow back” person from OG Twitter), and my inbox was overflowing with emailed articles and notifications. The tool let me connect my newsletter subscriptions and get AI-powered digests on demand that surfaced high-scoring articles with summaries while listing everything else, organized by category.

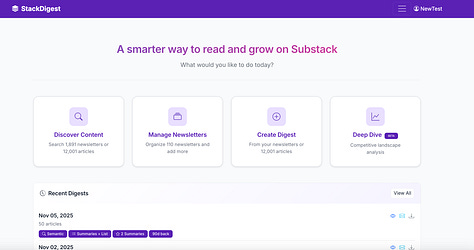

But it evolved into something much more ambitious. By the end, StackDigest offered:

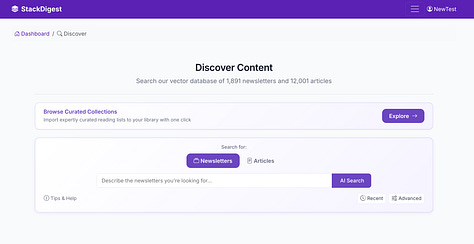

Semantic search, powered by OpenAI embeddings, that indexed 3,000+ newsletters and 55,000 articles for quick and easy newsletter and content discovery

Scheduled digests that ran once, daily, or weekly, and were automatically delivered to your inbox

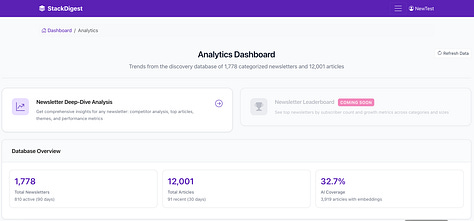

Analytics showing platform-wide publishing patterns, engagement trends, and competitive benchmarks

Deep Dive reports that used machine learning clustering to identify themes in individual newsletters’ content and compare their performance to similar publications

How StackDigest evolved

StackDigest evolved quickly in response to user feedback. This timeline shows how it went from idea to Python script to full-featured production-grade app in just a few months.

August 2025: The viral note

After struggling with newsletter overload for two weeks, I wrote a Note about a hypothetical digest tool. It got 104 likes and 28 replies, which was more engagement than anything else I’d ever posted. That was my validation signal.

August 9: Writing the first Python script

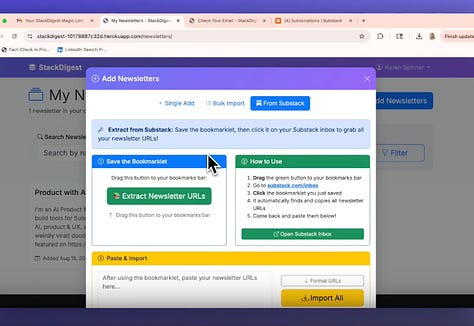

I built a basic Python script that grabbed newsletters via RSS feeds and created simple digests. I shared the code on GitHub and wrote about the process. People were interested, but RSS feeds had limitations. They failed intermittently, so some articles were missing, and engagement data (likes and comments) wasn’t always captured accurately.

Note: If you want to create your own DIY digests on your local machine, use this GitHub library, not the one linked above.

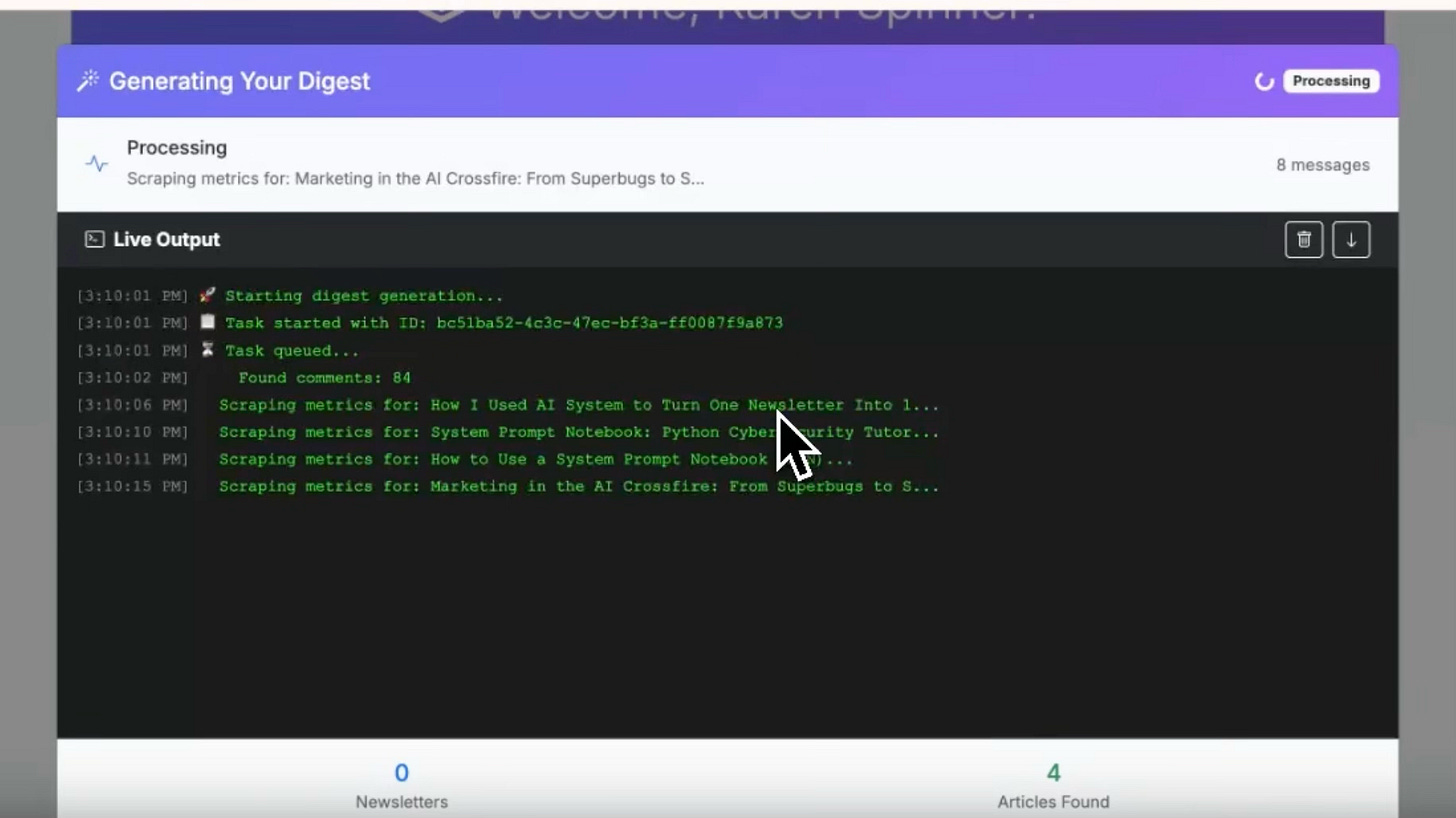

August 15: MVP launch

I turned the script into a web app in just five days. This involved reacquainting myself with Celery and REDIS for background processing, so digests wouldn’t time out for users with large newsletter libraries. I also had to connect the Celery back-end to a JavaScript polling function so users could get real-time progress reports on digest generation.

Late August: Discovering Substack’s undocumented API

To make digests more reliable and capture more engagement data, I started using Substack’s undocumented API. This really helped to improve the speed and accuracy of newsletter digest generation…and it was also the beginning of my compliance issues.

September 5: Switching to Claude Code and surviving a server crash

After building with Console Claude for over a year of using cut-and-paste, I finally tried Claude Code. It allowed me to fix bugs and add new features much more quickly. I also used it for things like app-wide security reviews and hunting for memory leaks.

Around this time, a server crash at my hosting provider nuked all of my user data. I went from 28 users to 0, and I upgraded to a hosting account with automated failover and backups.

Mid-September: Adding search

I first added keyword search via the Serper API for newsletter and article discovery, but it wasn’t great at surfacing quality content. Search results tended to include a lot of dead newsletters and articles optimized aggressively for SEO. And there was no way to tell if the newsletter had a reasonable track record without clicking through. Digests based on keyword search results weren’t much better. I had to go back to the drawing board.

Late September/Early October: Building the vector database

I pivoted to semantic search using sentence transformers from Hugging Face and created a PostgreSQL database with pgvector extensions and embedded 2,000 newsletters and 30,000+ articles. This worked great locally, but failed hard in production.

The huge dependencies required for sentence transformers to run immediately blew through my Heroku “slug” disk space limit. After spending a day on the problem, I discarded the sentence transformers in favor of OpenAI’s API endpoints. I had to rewrite a bunch of the code, but it scaled much better. Processing all my embeddings cost me just 36 cents.

October 4: The analytics breakthrough

I quickly realized the vector database had the potential to identify publishing trends across the Substack platform. I launched a feature using clustering algorithms that surfaced content themes and engagement trends for different types of content.

I shared some of my findings in my most popular article ever: I used machine learning to make sense of 39,000 Substack articles. The insights fascinated people, and I started to wonder if my users were more interested in discovery and analytics than digests.

Mid-October: Designing the Deep Dive report

User surveys and behavioral data, which I shared with Product Release Notes, confirmed my growing suspicions that the newsletter digest and discovery features were “nice” but “not sticky,” while creator analytics, especially if they could say something actionable about individual newsletters, were something users might care deeply about.

I built a personalized analytics feature I called (unoriginally) the Deep Dive report that analyzed a newsletter’s content using machine learning clustering, found the 50 most similar publications in the Substack ecosystem, and identified the highest-performing articles and themes. I tried it myself and shared it with a couple of users; it felt solid.

Late October: The moment of truth

The weekend I launched the Deep Dive feature, my production environment crashed from too many concurrent users. It was thrilling…and somewhat terrifying as I fixed bugs and reallocated server resources on the fly. (Thank you to

for testing my fixes early on a Saturday morning!)Excitement and caution

I was excited to see that the tool was “having a moment” and wondered if this could be the time to really transition from project to product and try to get some visibility outside my small corner of Substack. That might have looked like a Product Hunt launch, creator partnerships and sponsorships, and even running some ads.

But all that was going to require time and money. It would have also opened my tool to a lot more scrutiny. I wanted to make sure no fatal flaws were lurking behind the scenes (a TOS violation? A bad security bug?) that would turn my launch into a cautionary tale.

My first step was to take another look at the Substack terms of service (TOS). While I’d read it a few months ago when I started building StackDigest, at that stage, I was only using RSS feeds as the basis for digests and reading lists. And, unfortunately, I didn’t give it another thought as I focused intently on solving user problems and meeting demand.

When I finally opened the TOS again and made a point of reading it closely, my heart sank. It looked like I was operating in some murky areas, and scaling up could easily push me over the line. I ran my concerns by a lawyer, and he confirmed my worst fears.

It was time to shut things down.

The potential compliance issues

Now, before I walk through these, I want to stress that I am not a lawyer, and I am not providing legal advice. Don’t make decisions about your software projects based on these notes. Find your own lawyer and get advice tailored to your specific situation and risk tolerance.

All that said, here are some general areas that might have been problematic for StackDigest if I were to have gone ahead with a launch, or even continued to operate the tool in its final state without written permission from Substack.

Scraping/spidering

Per Substack’s TOS: “[Do not use Substack in a manner that] “Crawls,” “scrapes,” or “spiders” any page, data, or portion of Substack (through use of manual or automated means).” This language is broad, seemingly all-inclusive, and could easily be interpreted to cover everything from accessing content via Substack’s API to copying a Note to your desktop for future reference.

Using the undocumented API at scale

While Substack’s undocumented API is the basis for several GitHub projects and seems to be fairly widely known to developers, Substack does not have an official developer program or other mechanism for approving developer access. This means there is no consent for use of the API and, just as important, it could be changed or blocked at any time, which could have seriously compromised product functionality.

Dependence on this undocumented API without Substack’s explicit consent would also have been a dealbreaker had I ever looked for pre-seed investment. And RSS feeds were not an ideal substitute in terms of data coverage or reliability.

Copying and/or storing content

The TOS also has specific language about accessing larger amounts of platform content: “[Do not use Substack in a manner that] Copies or stores any significant portion of the content on Substack.”

I was collecting large amounts of newsletter metadata and, in some cases, freely available article content, to power search and digests. One idea I heard was to get rid of any article content while keeping embeddings for analysis and search. But the TOS language is broad. Would processing an article to generate an embedding be considered “copying?”

Because there is no official developer program, there is no way to know for sure what is or is not permitted.

All of these potential issues taken together felt like a multi-headed hydra of risk. And that, for me, wasn’t sustainable. Shutting down was an easy decision.

What I did wrong

Surprisingly, this list isn’t as long as I’d feared. And I was heartened to realize that I had made entirely novel mistakes relative to my previous product development experience.

But, without further ado:

⛔️ Built with an undocumented API for a platform with no formal developer program

Many platforms, like Reddit, Twitter/X, and others, offer access to their content via API, and there’s usually some kind of fee or approval process, depending on what you’re doing. Many others are free, at least up to a certain threshold of usage.

These APIs have well-documented endpoints, rules for accessing them, and resources that explain what you can and can’t do. This makes it much easier to know if you are in compliance, and there are people you can ask if you’re not sure.

⛔️ Allowed excitement for building the next cool feature to distract me from other issues (like the TOS)

I got so caught up in the excitement of building and responding to user feedback that I lost sight of legal and compliance concerns altogether, especially as my feature set evolved. If your application relies heavily on a third-party platform, it’s important to review the TOS every time you add a new feature.

Also, keep in mind that the TOS can change at any time, and consider building fallback strategies in case a critical API becomes unavailable or prohibitively expensive to use.

⛔️ Did not set up a limited liability corporation

I assumed this was overkill for a single developer building a tool I was sharing with a handful of followers. But once I had 50+ users and multiple feature sets, and a general commitment to growing the tool as much as I could, it was probably time. This is definitely something I will consider the next time a project starts to gain traction.

⛔️ Used hosting services that were too expensive

During my very first development project about a year and a half ago, GPT 3.5 recommended I use the Django framework and run it on Heroku with Celery and REDIS. It took a long time to figure this out, but once I did, I used it for all my projects. And, for StackDigest, it was a costly decision. Even though traffic for most of its life was very intermittent, I was paying for workers even when nobody was using them.

After reading up about more modern hosting services that can scale workers up and down in response to demand, I’m going to switch up my tech stack and hosting strategy.

What I did right

But I didn’t do everything wrong. I also did a lot of things right, especially:

Listened to and acted quickly on user feedback

Unlike Good Bloggy, where I built in isolation and ended up with no users, I validated StackDigest with a Note before writing a single line of code. Then I invited every commenter to beta test, and had conversations with everyone who responded. This is a big part of why I was able to attract 165 users with no marketing budget.

Pushed new features when they were just functional enough

I didn’t wait for perfection. The MVP launched in 5 days, I released features with known bugs, and I sometimes delayed bug fixes in favor of developing new features. This kept the feature-feedback cycle brisk.

Transparently communicated about bugs and flaws

When the production environment crashed and I lost everyone’s data, I sent DMs and posted Notes about what happened. When RSS feeds didn’t capture all articles, I explained the limitation. When I discovered better solutions, I shared both the problem and the fix. This built trust, and users became true collaboration partners.

Thought about production from day one and built code for asynchronous processing

While, in hindsight, Heroku, Celery, and REDIS were probably the wrong tech stack for StackDigest, I was able to implement them easily and quickly by keeping production constraints in mind as I built the code. Anything that could be processed in the background was processed in the background.

Continually refined the UI and UX

Based on feedback, I completely reworked the digest generation screen, added one-click newsletter import, and simplified the analytics interface. Every iteration made the tool more intuitive.

Made the tool an anchor for stories about AI, ML, and vibe coding

Every technical challenge became an article. The database build. The semantic search implementation. The machine learning clustering. This helped attract curious users organically, many of whom became actively involved in the project.

Technologies I worked with

During the course of this project, I learned a lot about machine learning and database development, as well as how to scale a production environment. Here are some of the technologies that I used, even if one didn’t make it into production:

Celery and REDIS for background task processing

PostgreSQL with pgvector for vector database implementation

OpenAI embeddings API for semantic search

Sentence transformers (which didn’t work in production)

Machine learning clustering algorithms (DBSCAN, medoid selection)

Semantic similarity analysis and cosine distance calculations

Django for web application development

Data pipeline architecture for processing tens of thousands of records

🤩 The amazing beta tester hall of fame

Working with the wonderful people who were willing to test StackDigest was the best part of the whole experience. They transformed a solo project into a genuine community effort, and their insights shaped the tool in ways I never could have imagined alone.

You know what’s coming…I want to thank the following people:

: Thank you for being the first beta tester. You have a great eye for bugs and presented some of the edgiest edge cases—the kind that only show up when someone actually uses the tool rather than just testing it. It was a delight to help surface the SWAI articles, and I hope we can get an open-source solution working for you soon.: You were one of the very first users and stuck with the tool even after a server crash wiped all the data. Your consistent insights and regular support really helped me get this off the ground! You also inspired me to combine data from the tool with NotebookLM—that Deep Dive + NotebookLM integration became one of my favorite features.: Your incisive UI-UX feedback helped shape the tool into something genuinely useful. You pushed me to think beyond “does it work?” to “is it actually pleasant to use?” You also had big ideas that inspired some of the most successful features—search and analytics. And you were endlessly patient with a wide range of bugs, always framing feedback constructively.: You helped troubleshoot the onboarding sequence (or lack thereof!) and identified blockers like the old bookmarklet that were discouraging people from using the tool. Your perspective as someone coming in fresh helped me see all the assumptions I’d made that weren’t obvious to new users.: You came up with strategic use cases for StackDigest that I hadn’t even thought of, like using digests to monitor competitors, shared insightful feedback about the UX, and helped me spread the word. : Thank you for being an early advocate of the tool and giving it lots of time in the sun on your StackShelf app and in your vibecoding content. Your example inspired me to start development in the first place—seeing what you’d built made me think “maybe I can do this too.” And I’m looking forward to sharing a few more vibe coding don’ts that I learned the hard way!: Your enthusiasm and willingness to help me spread the word—which included making a demo video and posting it as a Note—was greatly appreciated. It meant a lot and gave me confidence that the tool was valuable and might have the potential to grow!: The amazingly thoughtful interview questions you asked as we prepared a spotlight article for Product Release Notes helped me work through some product-market fit challenges. Sometimes you don’t fully understand your own product until someone asks you the right questions.: Your encouragement and insights throughout the journey helped keep the excitement alive. And you brought StackDigest to a whole new audience by featuring it—and what turned out to be the start of my epic struggle with sentence transformers 🤣—in Build to Launch.: Thank you for providing technical advice in the early stages while I was trying to nail down the basic functionality. You offered helpful insights and challenging questions that helped me think critically about my technical choices.: Your technical insights and encouragement were much appreciated as I tackled problems that were wildly beyond my skill level. I can see why you’re finding success as a mentor!: Thank you for all the kind words of encouragement and for bringing StackDigest to the attention of your readers. You also helped spread the word about the 5 Under 500 series and the creators featured therein, which meant a great deal to me and the featured writers.: I’ve always admired your work on tools that make it easier for Substack creators to grow, and the note you shared about the Deep Dive feature really made my day, after frantically debugging the production server.: You tested the very earliest version of the tool and suffered through the bad version of the bookmarklet…and came back and tested it again. You even provided an organized Google doc highlighting all the bugs. It was AMAZING, thank you!: You tested the tool at multiple stages of development and shared regular support, encouragement, and confirmation that it was still working…something that, after a few battles with server settings, I never took for granted! 🤣There were many others who tested, provided feedback, reported bugs, and cheered me on. Every bug report, every suggestion, every “this is actually useful” message made the late nights and frustrating debugging sessions worth it. If I’ve missed anyone here, please know I was VERY grateful for your help.

What’s next

StackDigest proved I can now build things I couldn’t have imagined building a year ago.

I shipped a genuinely useful product, validated demand, built in public, iterated based on feedback, and created something that—aside from the epic TOS fail—I’m pretty proud of. Those are real wins, and I carry them with me to whatever comes next.

I’m already scoping something new. 🫡

Excellent article, Karen!

I have a graveyard of 100+ projects that never reached the level you achieved on your 2nd one. But I'm a slow learner and need more repetition 🤣.

The good news is that the lessons (and even code snippets) can be re-used in the next projects.

Once you figure out Django and Jinja2 templates, building next website is much easier.

This whole experience just shows what a great product person you are, Karen. You’re so complete as a builder and have such a wide range of skills that I’m sure will take you far. So really I just want to say I can’t wait to see what you build next. I'm sure it'll be amazing. Count on me to cheer you on and help however I can.